By Lina Gerle

As Finland celebrates 100 years of independence this year, festivities will be mixed with contemplation of the country’s dramatic history, which has involved complicated relationships with its neighbouring countries, bloody battles and other momentous events which led up to the declaration of independence on December 6, 1917. I decided to delve into Gale Primary Sources to see what I could find out about this tumultuous history.

Sweden and Russia have played big parts in Finnish history; relations with both countries span centuries coloured by periods of intense conflict, as well as relative harmony. On February 21, 1808, the Russians invaded Finland – which at that point was a part of Sweden. In May of the same year, the important fortress Sveaborg was captured by the Russians. Although the Swedes/Finns managed to resist for another few months, this event has come to symbolise the loss of Finland to Russia and the beginning of a long period of Russian rule over Finland. A vivid depiction of Sveaborg and its setting is found in an article in The Illustrated London News Historical Archive nearly 50 years after the event, together with a description of this loss as ‘a dark day in the annals of Swedish and Finnish History’.

Although the beginning of this period was described as a ‘dark day’, Finland’s period as the Grand Dutchy of Russia included some great economic developments, and big investments were made in infrastructure such as railroads and ports. Finnish society also experienced rapid population growth, industrialisation, and the rise of a comprehensive labour movement. Plus, the country’s political and governmental systems were being democratised and the people’s socioeconomic condition and national-cultural status gradually improved.

It was also, however, during the nineteenth century that Finnish Nationalism grew stronger. The Finns were increasingly feeling that they weren’t Swedish, but that they didn’t want to become Russians either. Cultural expressions such as music and literature became more important than ever. Indeed, one of the most significant works in Finnish literary history – the Kalevala – was produced during this period. A beautiful translation of this work from 1893 is found in Gale’s Nineteenth Century Collections Online: Children’s Literature and Childhood. The preface outlines the significance of this piece of literature, and the then perceived situation for the ‘liberty-loving’ Finns.

Although the ‘iron hand of Russian nepotism’ was closing in on Finland, the ‘unforeseen’ which sometimes happens and which would make possible a ‘brighter future’ for Finland was only a little over 20 years away.

When the declaration of independence was adopted by the Finnish Parliament in December 1917, Russia was busy dealing with her own revolution. In fact, Russia/the Soviet Union was one of the first to acknowledge Finland’s independence! Sweden followed shortly, and in this article from The Telegraph Historical Archive, the Swedish King Gustaf’s response to the Finnish request for recognition shows how close the relationship between the two countries was – as well as how important a stable relationship between Finland and Russia was to the Swedes.

The declaration of independence in 1917 was the beginning of Finland as it is today, but it was only part of a much longer process leading to a truly independent Finnish Nation, including a dramatic civil war between the communist ‘Reds’ and the pro-German ‘Whites’ between the January 27 – May 15, 1918. Around two months into the war, an article in The Times Digital Archive give witness of this turbulent time and although no ‘winner’ had been crowned, signals of the coming victory of the ‘Whites’ were strong.

Once internal affairs had stabilised, Finland’s relationship with the West grew stronger – especially with Sweden and Britain, but tensions remained with what was then the Soviet Union. During the Second World War, the Finns had to protect their independence twice – first during the Winter War of 1939-1940, and shortly after in the Continuation War of 1941 – 1944.

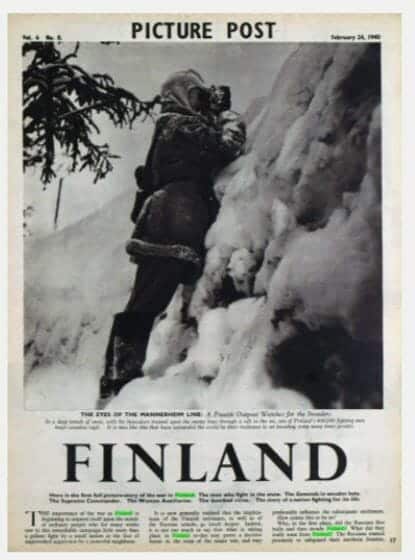

The harsh conditions under which the Finnish people had to fight can hardly be better conveyed than by this photograph from The Picture Post Historical Archive on February 24, 1940.

A description of the hardships and struggles the Finns have experienced defending their independence over the years is also clearly conveyed in this special report in The Times Digital Archive which marked the 50th anniversary of independence.

Having seen another 50 years pass since then, and with a hundred years of turbulent independence behind them, let’s hope that Finland can enjoy a more stable and harmonious time in the century ahead.