│ By Maya Thomas, Gale Ambassador at the University of Oxford │

From Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind to Elizabeth Swann in Pirates of the Caribbean, it seems that no pretty woman in a historical drama is complete without participating in the infamous “corset scene”. You know the one: the beautiful protagonist reluctantly sucks in her stomach, gripping onto the bedposts as a maid furiously tugs at her corset strings. We watch with morbid fascination as her tiny waist is made tinier still, compressed painfully in an ornate whalebone cage.

This perception of nineteenth-century women’s fashion as painful, torturous and unyielding in the pursuit of beauty is not just limited to films, it is pervasive throughout modern literature and art as well. However, as someone obsessed with costume history (my favourite book is genuinely about historical underwear…) what I find most alarming is that even in academic circles, corsetry is often viewed through the intellectually fatal lens of oversimplified negativity. Even when revealing my interest in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century costume history to one of my Oxford tutors, I was met with the usual response: “I can’t believe women were forced to wear such tight corsets all the time. No wonder they could hardly move or breathe! How sad…” (Readers who know me personally can probably hear my exasperated sigh from miles away…)

My tutor is not alone in her response. In most cases, our modern perception of corsetry as oxygen restriction in the name of beauty does not align with the average Victorian woman’s corset experience. Rather, it is based on the phenomenon of extreme tight-lacing – the deliberate practise of dramatically decreasing the waist circumference, sometimes, as in the case of Camille Clifford, to just eighteen inches! However, assuming that Clifford’s tiny waist was the norm at the dawn of the twentieth century is as inaccurate as assuming that in 2019 all women have undergone our own extreme beauty regimens – breast implants, “Brazilian Butt Lift” surgeries and lip fillers as encouraged by our own “Cliffords,” the Kardashians.

To help dispel the myths surrounding the corset, I decided to take to Gale’s archives. Perhaps looking at some primary sources would give me an insight into how my tutor’s modern, negative perspective on the nineteenth-century corset compares to that of its contemporary wearer.

When I entered “corset” into Gale’s Term Frequency tool, I immediately noticed a spike in documents published in the 1890s. With the movement for women’s liberation in full swing, the so-called “corset controversy” became a hot topic both within and outside the movement. Documents covering this discourse show that, to some extent, the torturous narrative of the corset is true. In 1889 for instance, the Manchester Times went as far as to blame the corset for the physical weakness of women:

However, I soon found that even amongst publications that were largely anti-corset, the discourse wasn’t one-sided. On the 5th of December 1889, the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel published an article in which women were asked to relate their opinions regarding the daily wearing of corsets. While a certain Madam Judic calls the corset an “iron prison”, she admits that “the bother of putting it on every morning is more than compensated for […] by the pleasure of taking it off every night”.

As I read my way through similar publications, I found that the main concern of corset wearers was not achieving the smallest waist possible. Rather than emphasising the extreme-hourglass figure they created, and that my tutor referred to with morbid fascination, corset advertisements heavily featured language like “health”, “support” and “comfort”.

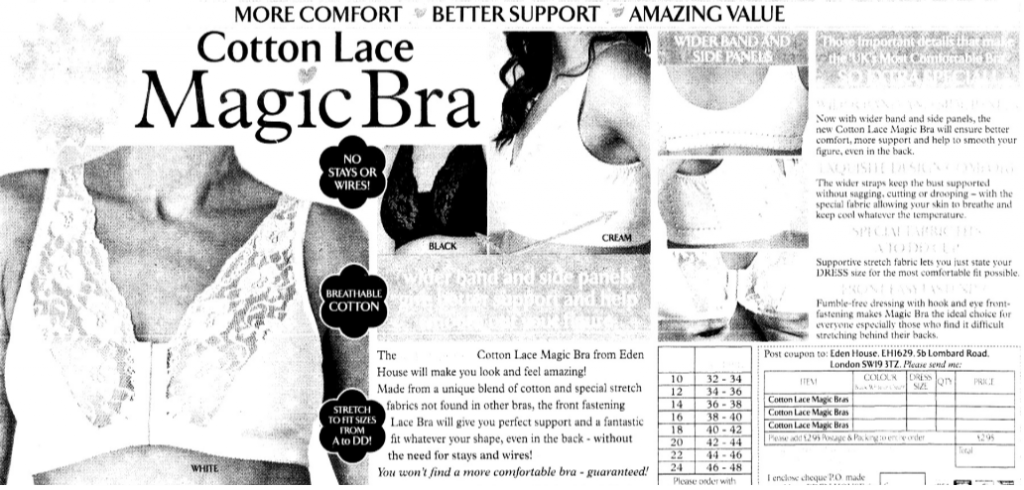

Reading several similar advertisements, I found this quite striking; it was like reading an advertisement for a modern-day bra! Thus it seems, a corset’s primary purpose, like that of a bra, was to provide the wearer with physical support that was flattering, but primarily practical, as this “Cotton Lace Magic Bra” advertisement in a 2013 publication of The Times shows below. Notice the similarity in the language!

So then, what is the truth behind nineteenth-century fashion? Well, it’s certainly not wrong to say that the creation of a small waistline may have been an aesthetic aspiration, but a look at Gale’s primary sources tells us that for most women, this was not necessarily the main concern. After all, with the strenuous work that was demanded from many Victorian women in the house, factory or farm, only a small minority could afford the luxury of the restrictive, tight-laced corsets worn by Camille Clifford. And so we see that the corset was not the terrible instrument of beautified torture that most assume it to have been. Rather, like any garment – historical or not – it balances precariously on the border between function and form. It’s up to us to decide into which category we feel it ultimately fell.

Blog post cover image citation: “DOUGLAS & SHERWOOD’S CELEBRATED TOURNURE CORSET. (Front view).” Godey’s Lady’s Book, 1 Apr. 1859, p. 296. American Historical Periodicals, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/OVABDO730659561/GDCS?u=webdemo&sid=GDCS&xid=9a3a45ac